In 1753 a new English law prescribed a formal ceremony of marriage that required brides and grooms to sign their names in a marriage register. The Marriage Act 1753, commonly referred to as Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage Act, was intended to regularise so-called ‘Scotch Marriages’. Happily for future researchers, it had the unintended consequence of bringing into being comprehensive and readily available data on adult literacy.

Someone’s signature on a register is a loose indication of their level of literacy. Though in itself a signature does not show that the signer had any general capacity to read and write, it does indicate that the person had achieved at least elementary reading and writing skills, and aggregated data on this can be used to expose patterns and trends in a population’s levels of adult literacy.

In 1861 the Registrar General for Births, Deaths, and Marriages in England asserted: “If a man can write his own name, it may be presumed that he can read it when written by another; still more that he will recognize that and other familiar words when he sees them in print; and it is even probable that he will spell his way through a paragraph in the newspaper.”

It has been suggested that person’s capacity to sign their name on a marriage register is an indicator of abiding literacy, for the signature was normally made more than ten years after the signer left school. Not all remembered what they had been taught: in the 1860s the Rector of Hornsea in Yorkshire complained that “they for the most part soon forget what they have learned at school and when they come to be married can’t write their own names”.

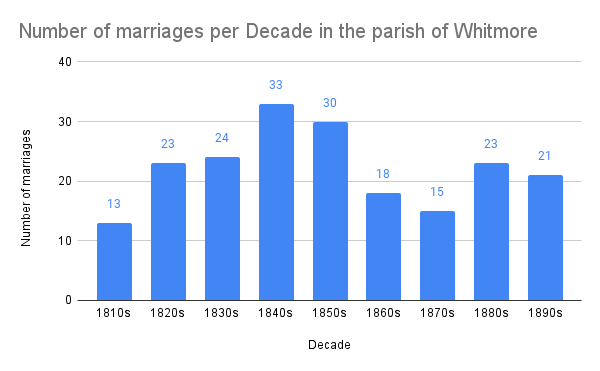

Marriage records of Whitmore parish from 1813 to 1900 are readily available. Those of marriages before 1813 have been combined with other records, making them more difficult to review.

I have tabulated the records from 1813 to 1900 to discover the proportion of brides and grooms who signed their names and the proportion who, unable to sign, made their mark an ‘X’ on the register.

I reviewed two hundred marriage records. In the 1810s 85% of grooms signed their name and just under 50% of brides. In the 1830s two-thirds of both grooms and brides signed their names. By the 1860s 95% of grooms and 90% of brides signed their name. By the end of the nineteenth century all grooms and brides signed their name.

While it was more likely that when only one signed it was the groom, there were instances of the bride signing and the groom making his mark.

the groom made his mark and the bride signed her name

The figures for Whitmore can be compared with statistics for the whole of England. In 1840 two-thirds of all grooms and half of all brides were able to sign their names at marriage. In the 1830s in Whitmore two-thirds of both grooms and brides could sign their name and in the following decade nearly all grooms and three-quarters of brides signed their name. By the end of the century the figure was 97% signed their name in England and Wales whereas in Whitmore all those who married in the 1890s signed their name.

It appears from these numbers that the average literacy of those who married in Whitmore was higher than the average for England and Wales. The data also suggests that the higher rate in Whitmore was achieved in advance of the passing of the 1870 Education Act, legislation that established the principle of a statutory responsibility for schooling, and helped achieve the rapid rise in UK literacy rates seen in the latter decades of the 19th century.

Related posts and further reading

- Stone, L. (1969). Literacy and Education in England 1640-1900. Past & Present, 42, 69–139. http://www.jstor.org/stable/650183

- Mitch, D. (1983). The Spread of Literacy in Nineteenth-Century England. The Journal of Economic History, 43(1), 287–288. doi:10.1017/S0022050700029326

- Stephens, W. B. (1990). Literacy in England, Scotland, and Wales, 1500-1900. History of Education Quarterly, 30(4), 545–571. https://doi.org/10.2307/368946

Wikitree:

While I’ve seen men making an x for a mark on wills… don’t remember seeing one making an x on marriage records. Now I’m curious… will have to check on several to see if I find one

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s interesting. My sister-in-law’s father signs his name with an X, but that’s just out of laziness.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had a great uncle born in 1900 who, through illness as a child and missing a lot of school, was unable to read and could only write his own name. He managed to get a motorbike licence and lived happily in the country most of his life. Life would be a lot more difficult for him nowadays.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great subject for your letter X post. I had two ancestors, Italian immigrants, who signed with an X when they married in New York City and a “her mark” and “his mark” next to their names. Nevertheless, they were an enterprising couple who raised a large family and operated a family business.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That seems to be a high level of literacy. I don’t think a study of the same time period in Australia would return similar results. I’m curious but too lazy to replicate your efforts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have good access to the local parish registers which made the analysis easier

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always look for literacy levels in my research. Interesting to see how the levels rose in the area you are studying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The level of literacy in Whitmore, seems to be quite high. Most of my ancestors couldn’t sign their own name. Except for my Scottish ancestors who could all sign. My 2x great grandfather was a parish schoolmaster and registrar, which would be the reason for their literacy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Scottish literacy rates were much higher than the English

LikeLike

Pingback: A to Z 2024 reflections | Anne's Family History