A “Quire” is the area of a Christian church, more often referred to as the chancel, where the choir assembles.

Thirty years ago we visited Durham Cathedral. We were very impressed by its magnificent stained glass, old and modern, the shrine to St Cuthbert, and also the tomb of the Venerable Bede, father of English history. The Norman architecture has survived largely intact. The stone columns were awe inspiring. Durham Cathedral was a place we remember fondly and are keen to revisit.

Nave of Durham Cathedral. Photograph from Wikipedia taken by Oliver-Bonjoch , CC BY-SA 3.0

The quire stalls and other woodwork in Durham Cathedral date from the mid-seventeenth century. The Cathedral, badly damaged in the Civil War, was rebuilt by Bishop John Cosin (bishop from 1660 – 1672). Cosin was responsible for a unique style of church woodwork, described as a sumptuous fusion of gothic and contemporary Jacobean forms.

Just after Easter when we were travelling in 1989 we were interested to read newspaper reports of the controversial theological views of the then Bishop of Durham, David Jenkins (1925 – 2016). Jenkins is remembered for raising doubts about the virgin birth and resurrection of Jesus. When we were driving in Scotland we saw a sign outside a Church of Scotland quoting the Apostles’ Creed “I believe in…the resurrection of the body”, which appeared to be a reference to the unorthodox theology of the Bishop of Durham.

We joked that the fortified position of Durham Cathedral high on the peninsula and surrounded on three sides by a river meant that the Bishop, well separated from the rest of the Christian community, would not need to be particularly circumspect in his questioning of fundamental Christian beliefs. One of Jenkins’s obituaries was entitled “David Jenkins: the bishop who didn’t believe in the Bible”.

Durham, ca. 1795, unknown artist, eighteenth century, , Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

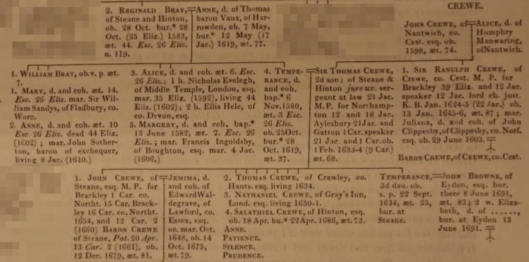

My tenth great uncle Nathaniel Crew (1633 – 1721), who succeeded John Cosins, was Bishop of Durham from 1674 to 1721, one of the longest serving bishops in the history of the Church of England. Like the twentieth century Bishop Jenkins, Nathaniel Crew was more than a little unorthodox. He is said to have owed his rapid promotion to the Duke of York (later James II), whose favour he had gained by secretly encouraging the duke’s Roman Catholic interests at a time, not long after the English Civil War, when the political role of the Church was being fiercely argued. James II was overthrown by the Revolution of 1688, the bloodless Glorious Revolution. Crew was not included in the general pardon of 1690 but was allowed to keep his see.

Nathaniel Crew in about 1680 by an unknown artist. Portrait in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Related posts

- Nathaniel’s grandmother: Temperance Crew nee Bray (abt 1580 – 1619)

- Nathaniel’s father and other family members: Samuel Pepys and the Crew family. Although I did not mention him in that post, Nathaniel is mentioned 5 times in Pepys’s diaries https://www.pepysdiary.com/encyclopedia/4186/ For example on 3 April 1667 Pepys recorded “Dr. Crew did make a very pretty, neat, sober, honest sermon; and delivered it very readily, decently, and gravely, beyond his years: so as I was exceedingly taken with it, and I believe the whole chappell, he being but young; but his manner of his delivery I do like exceedingly. His text was, “But seeke ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you.” ” [Matthew 6:33]

Sources

- Brown, Andrew. “David Jenkins: the bishop who didn’t believe in the

Bible” The Guardian, 6 September 2016 - Durham World Heritage Site https://www.durhamworldheritagesite.com/

- https://www.durhamworldheritagesite.com/architecture/cathedral/intro/quire