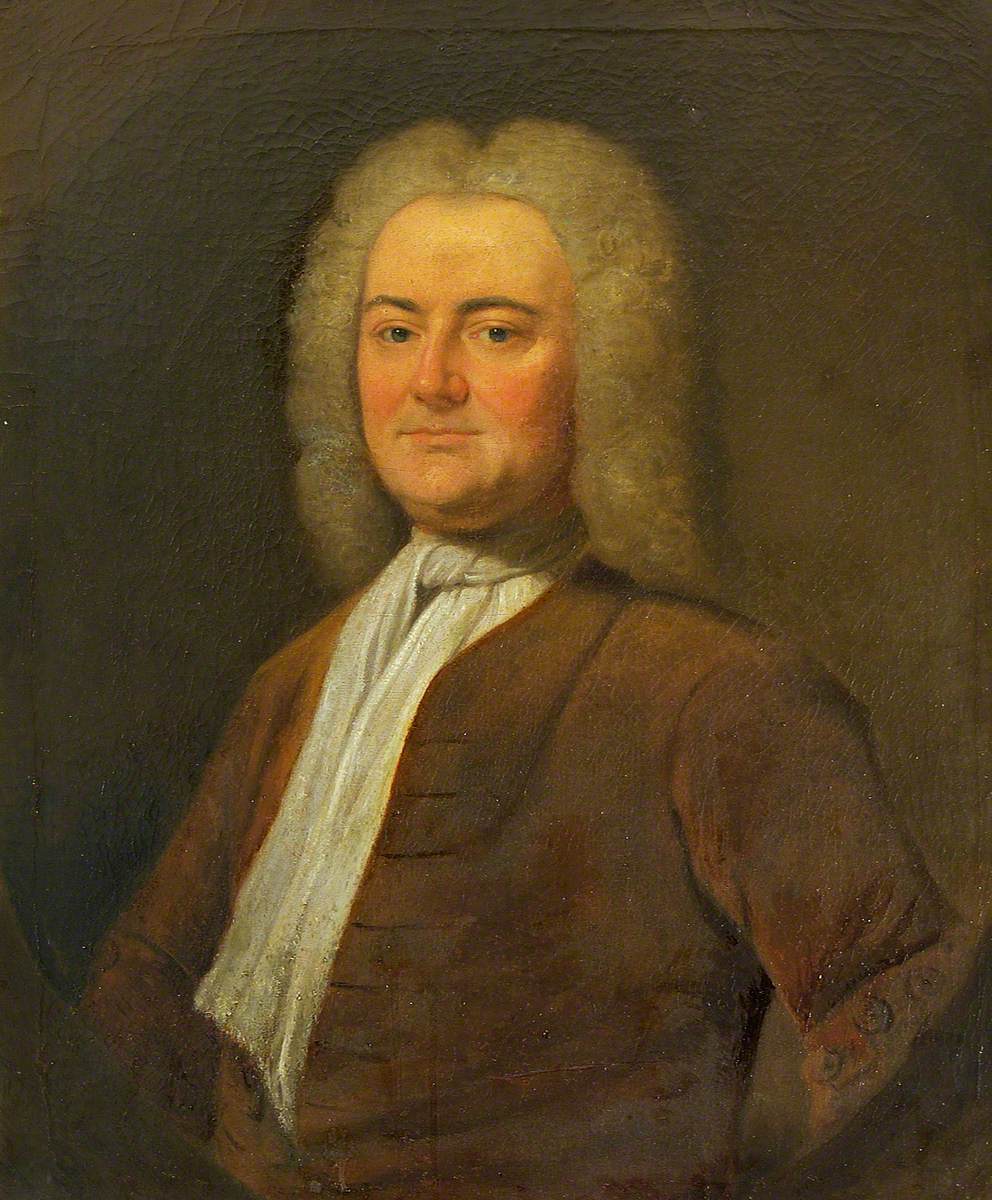

My 7th great uncle Pierre Champion (1653-1739), later known as Pierre Champion de Crespigny, was born in 1653 in Normandy, France, the oldest son of Claude Champion and his wife Marie nee Vierville.

In the late 1670s and early 1680s, the Huguenot congregation of Trévières found itself in dispute with the neighbouring church of Vaucelles. Pierre acted on behalf of the congregation of Trévières before the royal Council.

Within a few years of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, many French Huguenots found life increasingly difficult due to restrictions and persecution. Many emigrated including Pierre, with other members of his family, who left for England. In June 1687 he and his parents and his sisters Susanne, Renée and Jeanne/Jane were formally accepted into the French Church of the Savoy in London.

By an Act of 5 March 1691 in the English Parliament Pierre and his seven siblings became denizens of England. At this time the family surname was Champion. (A denizen was neither a subject with nationality nor an alien, but had a status similar to permanent residency. Importantly, a denizen had the right to own land. Denizenship was the forerunner of naturalization.)

Pierre was naturalized in 1705 with the surname Champion de Crepigny:

Peter Champion de Crepigny (Crespigny), son of Claude Champion de Crepigny, by Mary his wife, born at Vierville in Normandy, in France.

Pierre became a leader of the exiled community. He was a member of the council of the General Assembly of French Churches in London. This was an association of both conformist and non-conformist congregations which was especially active in relief and charity work. Pierre was also a founding Director of the French Protestant Hospital. Formally incorporated under royal charter on 24 July 1718 as “The Hospital for Poor French Protestants and their Descendants Residing in Great Britain”, it is commonly known as ‘La Providence’.

Director of the French Hospital La Providence 1718-1739

This is among a collection of shields which were formerly hung in the Court Room of the Hospital.

Though the shield is shown with a gold background to the first and fourth quarters and gold and black bars in the second and third, this is probably because of the material- brass or copper – from which it is made. The Champion/CdeC arms are a black lion on a white ground, and the Vierville family had blue and white bars; there is no reason to believe that Pierre used

different colours.

Source: Murchoch and Vigne, The French Hospital in England

Pierre was also assisted in the administration of legal affairs of members of the Huguenot community in London: there are several cases where he appears as a witness, as an executor, as maker of an affidavit, or as the provider of a certified translation. There is no evidence that he was formally licenced, but he was no doubt paid for his services.

Surviving letters to him and documents in his own hand were written in French, but he certainly was proficient in the English language.

He never married.

On 22 December 1739, at the age of eighty-six, Pierre died of apoplexy, a sudden stroke.

His will was made 10 August 1739 – it was translated into English for probate – after various individual bequests amounting to just over £1000, and the remainder was left equally to his nephews Philip and Claude, sons of Thomas. Besides giving money to his servant and his kinsfolk, Pierre gave £20 to the French Church of the Savoy and £20 to the Maison de Charité (House of Charity) in Soho.

Pierre asked that his body be placed in the family vault at Marylebone with that of his parents, and this was done on 27 December.

Related posts and further reading

- V is for Vaucelles v. Trévières

- F is for fleeing from France

- R is for refugees

- Murdoch, T. V. (Tessa Violet) & Vigne, Randolph & Murdoch, Tessa (2009). The French Hospital in England : its Huguenot history and collections. John Adamson, Cambridge

Wikitree: Pierre Daumont (Champion) Champion de Crespigny (1653 – 1739)

This post was created as part of Amy Johnson Crow’s 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks challenge. This week’s theme is “Language.”